Brexit’s new chapter: the ‘impossible’ trade deal

With just days to go before Brexit, European diplomats are already hard at work for the next phase: negotiations to hammer out a future with Britain after its EU divorce.

In the words of EU negotiator Michel Barnier, during the next phase of Brexit, Brussels and London will “have to rebuild everything”.

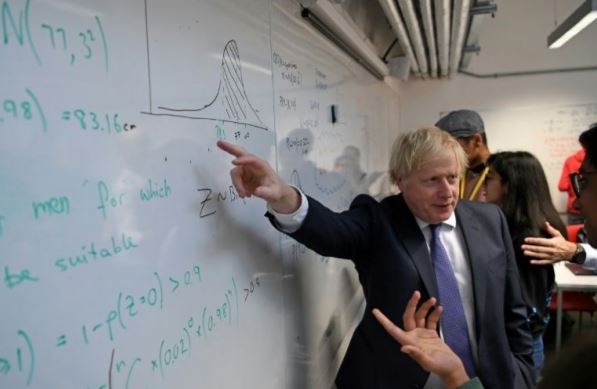

Prime Minister Boris Johnson seems reinvigorated after a clear electoral victory in December, but intense talks lie ahead.

Here are the main battle lines for the coming weeks:

No extension

Throughout his campaign, Johnson said he would seal a trade deal by December 31, the deadline set by the EU-UK divorce agreement.

London could request an extension of one or two more years if it decided to do so before summer, but Johnson insists it will not. This marked the EU’s first reality check -- only reluctantly accepted -- and Brussels officials no longer expect Johnson to ask for a delay.

That leaves only eight months, from late February to October, to reach an agreement and allow time for ratification.

“It’s an impossible task,” warned one European diplomat.

“By the end of the year, we could get the skeleton of a trade agreement plus something on internal and foreign security, but there is no guarantee,” the diplomat added.

Talks can begin as soon as EU ministers agree their joint mandate on February 25.

Johnson is not May

Johnson’s campaign promised “to get Brexit done” and to do away with his predecessor’s goals of close ties with Europe and minimal disruption to the cross-Channel economy.

Theresa May’s government had proposed a “dynamic alignment”, where London would find a way to match EU rules on the environment, state aid and other standards to guarantee UK companies easy access to Europe.

Johnson has pledged to instead pursue a far more minimal trade deal that will seek zero tariffs and quotas on goods, but make no binding commitment on standards.

“The prime minister has been clear that he wants a Canada-style free trade agreement with no alignment,” a UK official told AFP.

This refers to the EU’s trade deal with Canada that Europeans consider ambitious as a trade deal, but too narrow for an important neighbour like Britain.

“This is probably not the best time for them to make that decision,” warned Ian Bremmer, president at Eurasia Group.

“The UK does not have the size, does not have the technology does not have the competitiveness, does not have the diplomacy to really choose their future.”

Threat to unity

A tariffs-only trade deal would be a blow to Britain and a challenge to the UK’s closest trading partners -- such as Ireland, France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

No alignment on EU standards means custom checks, paperwork and all sorts of new limits to trade.

“Our first choice is that nothing changes,” lamented a diplomat. “But that is not going to happen, so we must now be realistic.”

Many in Brussels fear that Johnson’s low-bar strategy could be the biggest challenge to European unity since the Brexit referendum in 2016.

Member states will be pulling in different directions with some -- like France, Belgium and Denmark -- concerned about fishing access while eastern Europeans and Germany will want a deal on cars.

‘Zero-dumping’

Referred to as keeping a level playing field, member states with the most trade with Britain want to ensure that British companies gain no unfair advantage after Brexit.

When British goods and services come knocking on Europe’s door, they will insist that UK goods are subject to checks like those from any other nonEU country.

“Zero tariffs, zero quotas, zero dumping,” Barnier said.

Diplomats warn there were not many ways to enforce the level playing field in a simple trade deal, except through threatening tariffs that can take months or even years to impose.

The EU 27 have begun to draw up an elaborate arbitration process that could mean fines and suspension of any EU-UK accord if either side fell out of line.

‘Negotiation tables’

Months of intense discussions, to alternate between London and Brussels, will be coordinated by Barnier and his UK counterpart, probably David Frost.

The tight deadline allows “about 40 days of pure negotiation” in eight to ten-week sessions, an official warned.

This is a far cry from the years devoted to trade deals with Canada, Japan or South Korea.

Barnier said negotiators would open about ten “negotiating tables” in parallel.

“We will give each subject two or three weeks and see what is possible. If the divisions are too great, we move on,” a diplomat said.

Big deal?

One question nagging Europeans, notably France, is the future structure of the EU’s relationship with Britain.

Will it be something formal, with clearly set joint institutions, or a looser arrangement structured by separate deals on trade, security and other topics as necessary?

Many European capitals abhor the latter, spooked by the EU’s confused ties with Switzerland, which are governed by over 100 deals.

Related Posts