Does Canada need better gun control?

Last summer I taught a course at the University of Toronto called “American Tragedy: Guns and Mass Shootings in US History.” One memorable day, my 20 mostly Canadian students reflected on the frequency of mass shootings in America and how these calamities don’t receive much public interest unless the gunman claims several lives. One student remarked: “Reading about this stuff makes me so sad. It also makes me happy to live in Canada, where we don’t have to worry about this kind of thing.”

As an expatriate from California, I have felt this same sense of gratitude many times. Watching news reels and Twitter feeds about the next mass shooting back home, I would reflect that Toronto seemed immune to the kind of gun violence that I had witnessed and written about in Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

However, several gun attacks here this summer have made me, and many Torontonians, question that sense of exceptionalism. Mass shootings are no longer a uniquely American problem.

The latest occurred last week when, the police say, Faisal Hussain, 29, fired on diners sitting at outdoor tables along the Danforth, a bustling neighborhood near downtown. Reese Fallon, an 18-year-old woman set to study nursing this fall, was killed, as was Julianna Kozis, a 10-year-old synchronized swimmer. Thirteen more people were hurt. The city has also been gripped this month by allegations that a Toronto man killed at least eight people and buried them on property where he worked as a landscaper.

This incident came in the wake of a spate of other attacks. In April, 10 people were killed when the driver of a rental van in Toronto struck dozens of pedestrians on a sidewalk. In June, two men shot two sisters, ages 5 and 9, in a busy playground.

A friend on Facebook posted that she does not feel safe in Toronto anymore. I’ve caught myself ruminating in a similar vein; it’s hard not to, with the news dominated by multiple shootings, a mass van attack and a serial killer investigation.

Of course, it is important to put the violence into context. Not only is Toronto still a very safe city, it is one of the safest big cities in North America, with a homicide rate that has hovered around 1.3 per 100,000 over the past several years. This is much lower than Chicago (28.1 per 100,000) and Philadelphia (17.4 per 100,000), where I conducted years of gun violence research (New York is around 3.3 per 100,000). It’s also much lower than the most violent Canadian city, Winnipeg, which has a murder rate of about three per 100,000.

Still, the immediacy of the violence is changing the political conversation in the city. The shooting this past week has prompted some politicians — including Toronto’s mayor, John Tory — to reflect on whether handguns ought to be banned.

And that’s a good thing — because even if Canadian cities are safer than their equivalents in the United States, this country still has a gun problem.

The national statistical agency reports that 62 per cent of firearm-related homicides in Canada are committed with handguns. This flies in the face of most policy discussions after a mass shooting, which are typically associated with semi-automatic weapons like the AR-15.

Even though Canada requires gun buyers to get a license and take a safety training course, guns are still readily available, many of the same guns that you can buy in the United States. There are a few restrictions on magazine sizes and many concealable pistols are prohibited. But many other guns are as available here as they are south of the border.

Banning handguns in countries like Britain and Australia has led to significant drops in firearm-related injuries and death. Canada should consider a similar move.

This latest shooting also forces us to reflect on mental illness and the safety nets that exist for troubled young people. Even though Canada has a universal health care system, one that Canadians often hold in high esteem, there are still serious gaps in coverage. Long-term mental health care is often not covered by provincial health care. Many who need long-term support lack access to it (though to be clear, the man identified as the assailant in last week’s shooting was under a professional’s care for depression and psychosis).

People are still processing their fear and anger over this year’s violence. My concern is that we will fall back into the comforting stories about how safe Canada is; my hope is that instead, this time, we open the difficult conversation about whether civilians ought to own handguns, and what it would take to provide humane care for those suffering from mental illness.

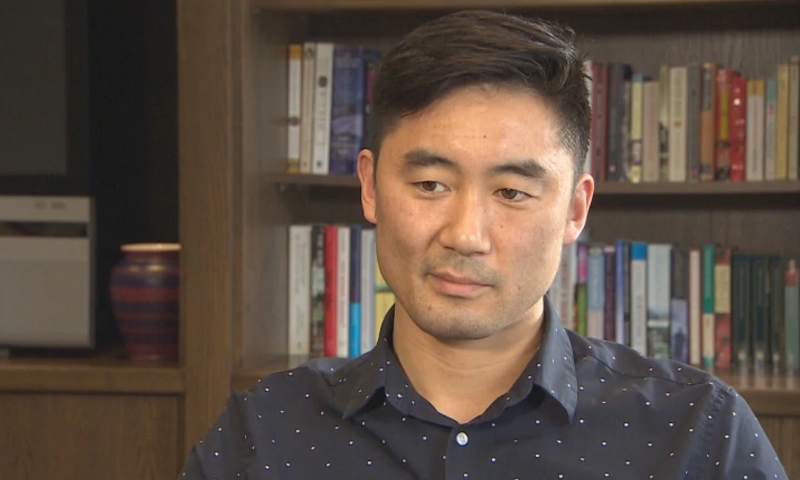

(Jooyoung Lee is an associate professor of sociology and faculty member at the Center for the Study of the United States at the University of Toronto.)

Related Posts