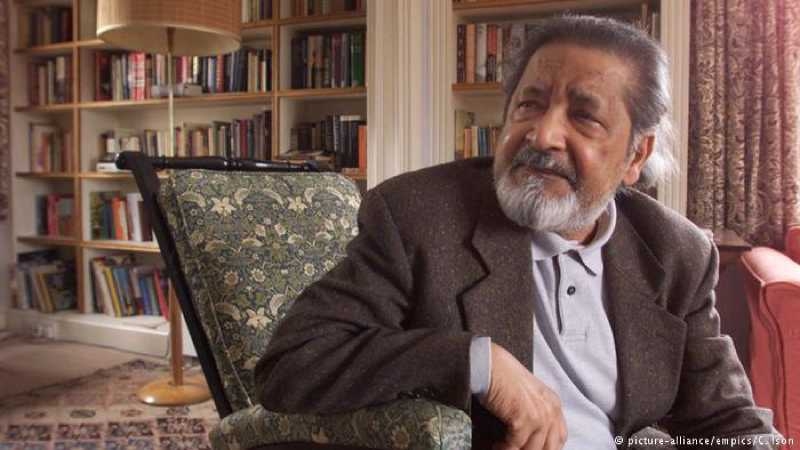

V S Naipaul, my wonderful, cruel friend

V S Naipaul, who towered over the landscape of post-colonial literature, died on August 11. He was my friend, my mentor, my teacher. I learned about his death from a one-line email from his widow, Nadira: “Vidia has gone gently into the night.” Vidia, as Naipaul was known to his friends, was born in 1932 in Trinidad to a family of Indian origin who had come as indentured labor after the abolition of slavery. Over a 50-year career, he gave young writers like myself — in India, in Africa, in the Islamic world and in South America — a searing glimpse of our own societies. At a time when the West was full of apology, and the non-West a sense of grievance, his great theme was the harm countries like mine would do themselves if they did not take responsibility for their histories. Through a quality of vision that was tantamount to cruelty, he showed the West how many of its assumptions were a celebration of its safety, while forcing us in the East to look hard at our places. There were many, including his contemporary and fellow Nobel laureate, Derek Walcott, who believed his concern was a form of contempt; Edward Said described him as an “intellectual catastrophe.” I adored him. His honesty set me free. I first met Naipaul when I was 18, and on my way to college in America. He told me not to go. “Indians,” he said, “they go to these places, they get dazzled by the institution and they come away having learned nothing but the babble.” “What should he do instead?” said my mother, who is a friend of Nadira’s. “He should go boldly into the world,” he replied. Over the next 20 years, he ran like a thread through the key moments of my life: the publication of my first book, the assassination of my father in Pakistan, my marriage to a man in America. I traveled with him and stayed with him. Our relationship was marked, as I believe all his relationships were, by a mixture of cruelty and tenderness. It was as if he saw a kind of freedom in reconciling people to the most severe version of the truth. In Wiltshire, England, where he lived since the 1980s, his tenderness and generosity were at the fore. He was safe, at home. And, in this mode, he was a wonderful teacher. He taught me about Japanese painting and Indian miniatures, about plants and trees in the countryside, which he immortalized in “The Enigma of Arrival.” The strain of brutality that ran through his thought came from a desire to be unassailable, to never, as he would say, “fall into lies.” When the truth came out, it could be crushing. He read and disliked my first novel. Even before publication, he was on the phone to me. I could tell from the thickness in his voice that he was in a brutal mood. “You haven’t understood the fictional form,” he said, “You have this ambition to write a novel, but you’ve really just loaded it with your own experiences.” For 90 minutes, he savaged me. Then he said, “I think you’ll make the transition to fiction very well. I wouldn’t be saying all this if I dn’t think that.” I was shattered. I remember feeling that my existence as a writer depended on my ability to survive the violence of this dressing down. “The trouble with Vidia,” Nadira wrote afterward, “is that he doesn’t give anything of himself, but when he does, then it is 100 per cent, and it can be unnerving.” What was true of the man was true of the work, too. In an epiphanic moment in “India: A Wounded Civilization,” in which a woman at a dinner party begins to tell Naipaul about how the poor are beautiful, “more beautiful than the people in this room,” his judgment arrives swift and bludgeoning: “The poor of Bombay are not beautiful,” he wrote, “they are like a race apart, a dwarf race, stunted and slow-witted and made ugly by generations of undernourishment; it will take generations to rehabilitate them.” I returned again and again to his work because I felt his version of my places — India and Pakistan — harsh as it was, restored a kind of autonomy. At a time when post-colonial studies was feeding us a great deal of comforting babble, Naipaul’s writing helped us take ownership of our past. He never looked away. I was with him in Wiltshire soon after my father, the governor of Punjab in Pakistan, was assassinated. I had been estranged from my father and was not sure how to mourn him. Naipaul, with an honesty that released me from guilt, said: “But your father was also your great enemy. So, his death must come with a feeling of relief.” It was something I would not have dared to think, let alone say. That honesty came alongside an immense and dangerous sense of humor. I’d been asked a number of times whether I thought my father had died for Pakistan. I was not sure how to reply. When I asked Naipaul what he thought, he paused for a moment then said, with a roll of that terrifying unsentimental laughter, “Better to say he died in Pakistan. Yes, yes, yes. Better to say that.” Naipaul paid a heavy price for his honesty. In India, many in the intelligentsia denounced him because they believed his politics were reactionary, that he gave cover to the Hindu right. But the truth is that the nuances of his positions were often lost. He was vilified by the left and co-opted by the right. But his work retains its complexity, and no one can come away from reading Naipaul with anything as simple as a political slogan. Yesterday, Salman Rushdie wrote, “We disagreed all our lives, about politics, about literature, and I feel as sad as if I just lost a beloved older brother.” As he slipped away, Nadira read to him from his work. Then she had a friend read him Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar.” “I did this,” she told me, “because his body had gone, but the mind would not let go.” It was devastating to hear. My relationship with Naipaul was full of its joys and hurts. It was never going to be otherwise; but, as he once said to me in relation to his brother’s death, “We do not control who we grieve for.”

Related Posts