These are not disposable allies as US thinks

The United States announced last month that it intends to keep troops in Syria to support Kurdish-led fighters there until the Islamic State has been completely routed and the area stabilised. Although this long-term commitment is critical, real stability and security can be ensured only by providing political recognition and practical support to the Kurdish administration governing northeastern Syria.

The United States has been backing the Kurds in Syria but has insisted on keeping the relationship strictly military. Since the first American weapons drop to Kurdish fighters besieged by the Islamic State in the Syrian town of Kobani late in 2014, Washington has focused on defeating the Islamic State and avoided statements or actions that could imply support for Kurdish autonomy or the Kurdish-led federation in Syria.

rn

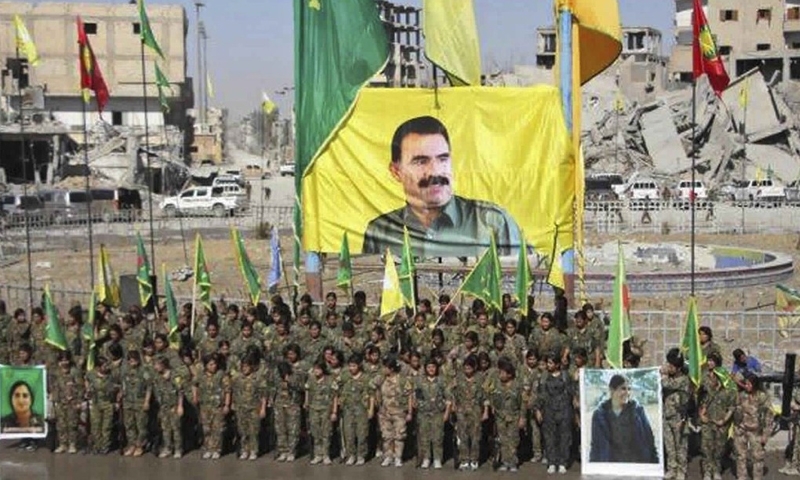

Today, largely thanks to the sacrifices of these Kurdish fighters from the People’s Protection Units, known as the YPG, Islamic militants have lost control over almost all of northeastern Syria, including their self-proclaimed capital, Raqqa. The last Islamic State stronghold, in Deir ez-Zor province, is under attack by Kurdish fighters and their umbrella Syrian Democratic Forces and will fall soon.

The Kurds now control more than a quarter of Syrian territory where an estimated 1.5 million to 2 million people live. They have created their own administration to govern and provide services. As part of their vision for a decentralized and inclusive Syria, their institutions operate according to rules that promote equal participation for women and equal representation for ethnic and religious groups.

Governing has proved difficult. Bureaucrats and others in the civil service, who, according to Kurdish officials, number some 190,000 people excluding the police, are often untrained and inexperienced. Combined with limited funding and the continuing battle with the Islamic State, the Kurdish-led authority has found it hard to provide the necessary services to support the population and foster stability.

The Kurdish region faces an additional challenge in the de facto embargo that is imposed on it by its neighbors and the rest of the world. Turkey has closed its border with the area and even blocked off portions of it with a concrete wall. Opportunities for trade with neighboring Iraq or the rest of Syria are severely limited. International aid, such as from the United States and Europe, goes mostly to refugee camps or the Arab areas around Raqqa or Manbij and ignores majority-Kurdish areas. This weakens the administration and paralyzes economic development.

Washington has hesitated to recognize the ruling authority as the legitimate governing body for the area it controls because the YPG and its main political arm, known as the PYD were created by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, the Turkish Kurdish group fighting a decades-old insurgency against Turkey. Both Turkey and the United States list the PKK as a terrorist group.

There are good reasons to criticize the Kurdish leadership. The PYD and the associated political and military institutions exert tight control in northeast Syria. Its administration harasses opposition parties, few of which still operate.

Yet aiding the Kurds militarily and ignoring them politically doesn’t promote a more politically tolerant society, nor does it encourage stability. The only way to build an alternative to the chaos and repressive dictatorship in the rest of Syria is through recognition of the Kurdish-led administration andactive political engagement.

The United States can use its support as a lever to push for a more open system in the Kurdish-controlled areas. The United States can include opposition and independent activists in political meetings in northeastern Syria, and it can demand the administration lift regulations that impede activities by groups and individuals not part of the self-rule authority’s affiliated political organizations.

At the same time, the United States and the European Union should help the Syrian Kurds on technical issues, such as water and sewage. They should help to train a professional bureaucracy that works on the basis of competence and skill rather than on party loyalty.

Political engagement could not come at a more critical time. President Bashar Assad has retaken control of most of Syria. He wants next to move against Idlib, the last major rebel stronghold, where some three million people live. Hisplanned assault was suspended last week — at least for now — under a deal brokered by his backer, Russia, and Turkey, which has supported rebel forces and fears a new influx of refugees.

The Kurds, unsure of Washington’s commitment to them, are hedging their bets. Although the YPG denied it would join an Idlib offensive, reports indicated that a token Kurdish force was prepared to take part. A Syrian regime assault on Idlib would help the Kurds by weakening Turkey, which this year invaded and occupied the Kurdish enclave of Afrin.

In the absence of American political support, the Kurds have had no choice but to make overtures to Russia — and to the Syrian regime. In July, a delegation from the Kurdish-led administration went to Damascus to start negotiations for a political settlement. An agreement seems far-off. The Kurds’ basic demand for a decentralized Syrian state that protects minority rights is not something Assad wants to accept. The lack of a political deal makes it that much harder for the Kurdish-led administration to create stable institutions.

It is the time for Washington to stop treating the Kurds as effective but disposable partners in the fight against the jihadis. The Kurdish experiment in Syria, however flawed, is a possible route to long-term stability. With assistance and recognition, the United States can salvage part of Syria, give the Kurds the backing they need to demand a fair settlement from Damascus and retain a base for future operations against violent extremists.

Related Posts