What is the future of IS female?

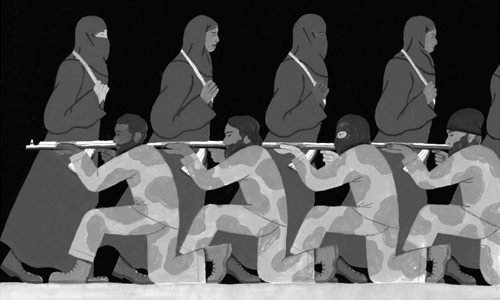

Sitting in a room in a burnedout house here in 2017, a group of Iraqi Special Operations Forces soldiers and I watched with surprise as two Islamic State fighters appeared on the live video feed of a security camera. The two fighters were preparing to fire a rocket-propelled grenade in our direction. But instead of the usual bearded men with long hair, the fighters, clad in black abayas and niqabs, appeared to be women. As it has lost power and land over the past year and a half or so, the Islamic State has quietly shifted from insistence on a strict gender hierarchy to allowing, even celebrating, female participation in military roles.

It’s impossible to quantify just how many women are fighting for the group. Still, interviews with police forces in Mosul suggest they’ve become a regular presence that no longer surprises, as it did two years ago. “After ISIS fell in Mosul, we are worried about ISIS females more and more,” Mosul’s mayor, Zuhair Muhsin Mohammed al Araji, told me this month. Islamic State propaganda over the past few years has hinted at and laid the groundwork for this change: In October 2017, the movement’s newspaper called on women to prepare for battle; by early last year, the group was openly praising its female fighters in a video that showed a woman wielding an AK-47, the narration describing “the chaste mujahed woman journeying to her Lord with the garments of purity and faith, seeking revenge for her religion and for the honour of her sisters.”

And if by some measures, the rise of women as combatants represents a significant shift in a group notorious for its strict gender roles and misogyny — in the caliphate, men were supposed to fight, while women were supposed to stay home and raise as many children as possible — by other measures, the change is not as startling as it seems. The women once married to Islamic State militants who are now seeking to return to the West may claim to have simply been housewives, but from the beginnings of the group, some women were more radical than their husbands. One former fighter from Dagestan told me he knew of women insisting that their husband or sons join the terrorist group. He also knew of women who did not want to marry anyone other than front-line fighters because “they wanted to be a true mujahedeen family.” For other women, their willingness to participate is driven by revenge, need or both.

The devastating battle for Mosul was followed by a post-liberation rampage by Iraqi security forces who harassed and raped women and looted their homes; many Islamic State widows are now willingly helping the insurgency just to get back at the government, people I’ve interviewed in refugee camps say. There are also many widows who, left without incomes and living in terrible conditions in refugee camps, feel they have no other choice but to work for the group so their family can survive. Although Islamic State propaganda bills the change as “a campaign that commences a new era of conquest,” the move to allow female combatants is born out of desperation.

The group has lost essentially all its territory. Most of its male fighters have been killed, wounded or arrested, according to Raid Hamid, chief investigative judge at the Mosul terrorism court. But an increasing number of voices have warned that the movement has the potential to be even more dangerous as an insurgency. And it’s in this form that rise of women as combatants as well as covert operatives gives the group an edge. When the Islamic State controlled huge areas, it had a well-defined military of men in uniforms. But for an organisation that increasingly needs to prioritise stealth, female operatives are a valuable weapon. After the fall of Mosul, for example, the forces I embedded with often saw women walking through the debris with food and water — an act that would have raised suspicions among the police had they been men, but which women could more frequently get away with.

As a result, militants who might otherwise have been forced out of hiding were perhaps able to stay alive. And some government security forces aren’t always prepared to address these changes in the Islamic State’s demographics. While there are women among the forces fighting the Islamic State in Syria, there are none in combat roles in the army and Special Operations Forces in Iraq. Their absence became a security issue during the operation to retake Mosul: While soldiers in the unit I was embedded with typically patted down the men coming from Islamic State-controlled neighbourhoods and checked them for weapons or explosives as they surrendered, the soldiers were not willing to touch the women.

That this made them more dangerous than the men was widely understood, according to Hussain Mahmoud, a colonel in the federal police. And it was women who were responsible for many of the suicide bombings that took place almost daily at Iraqi army positions during the Mosul operation, according to Lt Gen Abdul Wahab al Saadi, one of the leaders of Iraq’s efforts against the Islamic State. Al Araji, the Mosul mayor, said that police forces, who today provide most of the security for the city, are working on plans to recruit more female officers, and to add closed rooms to checkpoints where women can be searched — but said he is pessimistic about the timeline.

Civilians in Iraq are certainly aware of the new face of the Islamic State. According to a survey a colleague and I conducted in Mosul in December, 85 per cent of 400 respondents said that in the past, Islamic State women were as radical as men and 80pc agreed or strongly agreed that they played an important role in the group; 82pc said they agreed or strongly agreed that Islamic State women will be dangerous for Mosul in the future. If gender roles in Iraq were previously mostly a human rights concern, now they have also become a security concern.

A group notorious for its misogyny might be considered ahead of the country as a whole when it comes to gender equality among its fighters, and perhaps, too, in its willingness to see women as fully capable of causing destruction. Iraq will soon have no choice but to rethink its own ideas about gender roles, security and who can be a threat, if it is to keep itself safe.

Related Posts